Allosaurus (pronounced /ˌæləˈsɔːrəs/; meaning "different lizard") is a genus of large theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 150 million years ago during the late Jurassic period (Kimmeridgian to early Tithonian).

Allosaurus was first described in 1877 as Antrodemus, but it has since been renamed to Allosaurus after it was decided the original classification was based upon poor material.

Description[]

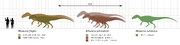

The size range of Allosaurus compared with a human

Allosaurus stood about 8 feet (2.4 metres) tall and measured about 28 feet (8.5 metres) long, though some remains suggest it could reach up to 12 meters (40 feet) depending on the species. It's three-fingered forelimbs were smaller than its large hind legs, and the body was balanced by a long, heavy tail.[1] It weighed 2-3 tons. The skull was narrow and had a pair of horns above and in front of the eyes.[2]

History[]

Allosaurus was first discovered in 1869 by Ferdinand Hayden and then named in 1877 by its founder Othniel Charles Marsh.

Remains of many individuals have been found, including some which are almost complete. Over sixty individuals from one species have been found.[3]

Paleobiology[]

Feeding[]

Artist's rendering of Allosaurus fragilis

Sauropods, live or dead, seem to be likely candidates as prey. Sauropod bones with holes fitting allosaur teeth, and the presence of shed allosaur teeth with sauropod bones have been found.[4]

There is dramatic evidence for allosaur attacks on Stegosaurus. An Allosaurus tail vertebra has been found with a partially healed puncture which fits a Stegosaurus tail spike. Also, there is a Stegosaurus neck plate with a U-shaped wound that correlates well with an Allosaurus snout.[5]

As the top predator of its age and habitat, Allosaurus hunted and scavenged whatever smaller or larger prey was abundant. However, it had a modestly-sized skull filled with slightly small teeth and was greatly outweighed by sauropods and probably preferred to hunt young, weak, old, sick, injured, or trapped sauropods over healthy adults. As sauropods were the dominant species of the time, they would be preyed upon by Allosaurus more often than not, with a common speculation being that this was done through hunting in packs, which it did to bring down any large prey that could put up a fight.

Researchers have made other suggestions. Robert T. Bakker compared the short teeth to serrations on a saw. This saw-like cutting edge runs the length of the upper jaw and could have been driven into prey. This type of jaw would permit slashing attacks against much larger prey, with the goal of weakening the victim.[6]

Another study showed the skull was very strong but had a relatively small bite force. The authors suggested that Allosaurus used its skull like a hatchet against prey, lifting its head up, with its mouth open, and crashing down on its prey. This 'Axe-bite' weakened the prey severely.

They suggested that different strategies could be used against different prey. The skull was light enough to allow attacks on smaller and more agile ornithopods, but strong enough for high-impact ambush attacks against larger prey like stegosaurs and sauropods.[7]

Their ideas were challenged by other researchers, who found no modern examples of a hatchet attack. They thought it more likely that the skull was strong to absorb stresses from struggling prey.[8]

The original authors noted that Allosaurus itself has no modern equivalent, so the absence of a modern 'hatchet attacker' was not significant. They thought the tooth row was well-suited to such an attack, and that articulations (joints) in the skull helped to lessen stress.[9]

Another possibility for handling large prey is that theropods like Allosaurus were 'flesh grazers' which could take bites of flesh out of living sauropods, sufficient to sustain the predator so it did not need to kill the prey outright. This strategy might have allowed the prey to recover and be fed upon again later.[10]

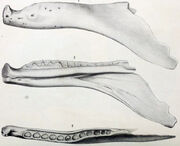

A. fragilis showing its maximum possible gape, based on Bakker (1998) and Rayfield et al. (2001)

Another idea is that ornithopods, the most common available prey, could be subdued by Allosaurus grasping the prey with their forelimbs, and then making bites on the throat to crush the trachea.[11] The forelimbs were strong and capable of restraining prey,[12] and the articulation of the claws suggests that they could have been used to hook things.[13]

The shape of the Allosaurus skull limited binocular vision to 20° of width, slightly less than that of modern crocodilians. As with crocodiles, this may have been enough to judge prey distance and time attacks.[14] The similar width of their field of view suggests that allosaurs, like modern crocodiles, were ambush hunters.[15]

Finally, the top speed of Allosaurus has been estimated at 30 to 55 kilometers per hour (19 to 34 miles per hour).[16]

Social behavior[]

The holotype dentary of Labrosaurus ferox, which may have been injured by the bite of another A. fragilis

Some palaeontologists think Allosaurus had cooperative behavior, and hunted in packs. Others believe they may have been aggressive toward each other.

Groups have been found together in the fossil record. This might be evidence of pack behaviour, or just the result of lone individuals feeding on the same carcass.

Allosaurus in The Land Before Time[]

Allosaurus is one of several dinosaurs that appear in The Land Before Time series, where it is one of several "Sharptooth" breeds that antagonize the main characters.

The first morph appeared in The Land Before Time VI: The Secret of Saurus Rock, where it serves as one of the antagonists of the film. The same individual also makes a minor appearance in a flashback in the television series episode, "The Lone Dinosaur Returns", along with another Allosaurus, which is actually a Tyrannosaurus in the movie.

The initial morph of Allosaurus in The Land Before Time franchise are brown, as opposed to green or olive like the early sequels' Tyrannosaurus. The theropod shares this colour scheme with some ceratopsians and sauropods seen in the franchise. While they also appear to use a similar model and body design to Tyrannosaurus they have some tweaks to better match their own species. This includes a slightly longer snout and ridged crests above their eyes. While Allosaurus had three-fingered hands, the individual that appears in the sixth film is incorrectly depicted with two fingers on each hand; however, in some shots, it is shown with the correct three, but, this is due to animation errors. The same error can be applied to the two individuals shown in the television series flashback, as they are shown with the incorrect, two-fingered hands.

The initial Allosaurus is also shown to be as large as Tyrannosaurus, however, this is not the case. Most allosaurs were quite small in comparison to the other theropod, but, Saurophaganax, a larger relative of Allosaurus, reached lengths up to 43 ft. Some fans have speculated that the Allosaurus seen in the film might actually be a Saurophaganax due to its larger size.

The second morph of Allosaurus is dramatically different from the one in the sixth movie; appearing in The Land Before Time XIV: Journey of the Brave, they are referred to as "Featherhead Sharpteeth", and are portrayed as colorful, four-fingered, extensively feathered theropods with blue nasal crests.[17] They bear a strong resemblance to the Chinese tyrannosaur Yutyrannus, and also resemble the crested Monolophosaurus. They are significantly smaller than their The Secret of Saurus Rock counterpart, being closer in size to the small Tyrannosaurus in The Land Before Time VIII: The Big Freeze than the tyrannosaurs from the earlier sequels.

Outside of The Secret of Saurus Rock and Journey of the Brave, the skeleton of what may be an Allosaurus makes a small appearance in The Land Before Time III: The Time of the Great Giving, during the climactic sharptooth fight.

Gallery[]

References[]

- ↑ Madsen, James H, Jr. 1993 [1976]. Allosaurus fragilis: a revised osteology. 2nd ed, Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 109. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey.

- ↑ Madsen, James H., Jr. (1993) [1976]. Allosaurus fragilis: A Revised Osteology. Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 109 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; and Currie, Philip J. 2004. Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds) The Dinosauria. 2nd ed, Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110. ISBN 0-520-24209-2

- ↑ Fastovsky, David E.; and Smith, Joshua B. 2004. "Dinosaur Paleoecology", in The Dinosauria, 2nd ed. 614–626.

- ↑ Kenneth, Carpenter; Sanders, Frank; McWhinney, Lorrie A.; and Wood, Lowell (2005). "Evidence for predator-prey relationships: Examples for Allosaurus and Stegosaurus". in Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 325–350. ISBN 0-253-34539-1.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T. (1998). "Brontosaur killers: Late Jurassic allosaurids as sabre-tooth cat analogues" (pdf). Gaia 15: 145–158. http://www.mnhn.ul.pt/geologia/gaia/10.pdf.

- ↑ Rayfield, Emily J.; Norman, DB; Horner, CC; Horner, JR; Smith, PM; Thomason, JJ; Upchurch, P (2001). "Cranial design and function in a large theropod dinosaur". Nature 409 (6823): 1033–1037. PMID 11234010.

- ↑ Frazzetta, T.H.; Kardong, KV (2002). "Prey attack by a large theropod dinosaur". Nature 416 (6879): 387–388. PMID 11919619.

- ↑ Rayfield, Emily J.; Norman, D. B.; Upchurch, P. (2002). "Prey attack by a large theropod dinosaur: Response to Frazzetta and Kardong, 2002". Nature 416: 388.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; and Currie, Philip J. 2004. Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds) The Dinosauria. 2nd ed, Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110. ISBN 0-520-24209-2

- ↑ Foster, John Wikipedia:2007. "Allosaurus fragilis". Jurassic West: the dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and their world. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 170–176. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8 OCLC 77830875

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth 2002. "Forelimb biomechanics of nonavian theropod dinosaurs in predation". Senckebergiana lethaea 82 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1007/BF03043773

- ↑ Gilmore, Charles W. 1920. "Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genera Antrodemus (Allosaurus) and Ceratosaurus". Bulletin of the United States National Museum 110: 1–159.

- ↑ Stevens, Kent A. (2006). "Binocular vision in theropod dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (2): 321–330.

- ↑ "Evolve: Eyes". History channel Evolve. Transcript.

- ↑ Christiansen, Per (1998). "Strength indicator values of theropod long bones, with comments on limb proportions and cursorial potential" (pdf). Gaia 15: 241–255. http://www.mnhn.ul.pt/geologia/gaia/19.pdf.

- ↑ https://www.gangoffive.net/index.php?topic=15588.msg475544#msg475544

External links[]

- Specimens, discussion, and references pertaining to Allosaurus at The Theropod Database.

- Allosaurus at DinoData.

- Utah State Fossil, Allosaurus, from Pioneer: Utah's Online Library.

- Restoration of MOR 693 ("Big Al") and muscle and organ restoration at Scott Hartman's Skeletal Drawing website.

- List of the many possible Allosaurus species...